Models are metaphors. They allow to see one thing in terms of another. Communication models are merely pictures; they are even distorting pictures because they stop or freeze an essentially dynamic interactive or transactive process into a static picture.

In the words of Mortensen, “In the broadest sense, a model is a systematic representation of object or event in idealized and abstract form. Models are somewhat arbitrary by their nature. The act of abstracting eliminates certain details to focus on essential factors…. The key to the usefulness of model is the degree to which it conforms-in point-by-point correspondence–to the underlying determinants of communicative behavior.” Owing to different approaches and different scholarly values, we need different models of communication. Therefore, model is a simplified representation of complex interrelationships among elements of communication processes that allow us to visually understand a sometimes-complex process.

1. Questioning: A good model is useful, then, in providing both general perspective and particular vantage points from which to ask questions and to interpret the raw stuff of observation. The ore complex the subject matter-the more amorphous and elusive the natural boundaries-the greater are the potential rewards of model building.

2. Clarify Complexity: Models also clarify the structure of complex events. They do this, by reducing complexity to simpler structures. Thus, the aim or a model is not to ignore complexity or to explain it away but rather to give it order and coherence.

3. New Discoveries: At another level models have heuristic value; that is, they provide new ways to conceive of hypothetical ideas and relationships. This may well be their most important function. With the aid of a good model, suddenly we are jarred from conventional modes of thought…. Ideally, any model even when studied casually, should offer new insights, and culminate in what can only be described as an “Aha!” experience.

1. Oversimplifications: There is no denying that much of the work in designing communication models illustrate the often-repeated charge that anything in human affairs which can be modelled is by definitions too superficial to be given serious consideration. of some experts place no value in models.

The risks of oversimplification can be guarded by recognizing the fundamental distinction between simplification and oversimplification. By definition, and of necessity, models simplify. So do all comparisons. As Kaplan noted, “Science always simplifies; its aim is not to reproduce the reality in all its complexity, but only to formulate what is essential for understanding. prediction, or control. That a model is simpler than the subject-matter being inquired into much a virtue as a fault, and is, in any case, inevitable.” So, the real question is What gets Simplified. This way, a model ignores crucial variables and recurrent relationships, it is open to the charge of oversimplification. If the essential attributes or particulars of the event the event are included, the model can generate overcarefulness to put everything that the simplest of two interpretations is superior. Simplification, after all, is inherent in the act of

abstracting. For example, an ordinary mango has a vast number of potential attributes; it is necessary to consider only a few when.one decides to eat a mango, but many more must be taken into account when one wants to capture the essence of a mango in a prize-winning recipe show.

2. Confusion: Critics also complaint that models are readily confused with reality. The problem of typically begins with an initial exploration of some unknown territory. Then the model begins to function as a substitute for the event: in short, the map is taken literally. And what is worse, another form of ambiguity is substituted for the uncertainty the map was designed to minimize. What has happened is a sophisticated version of the general semanticist’s admonition that “the map is not the territory.” Japan is not pink because it appears that way on the map.

3. Premature Closure: A model can be designed escaping the risks of oversimplification and confusion but abstraction, in built, can put it in hot waters. To press for closure is to strive for a sense of completion in a system. According to Kaplan, “The danger is that the model limits our awareness of unexplored possibilities of conceptualization.

Communication is a social process in which individuals employ symbols to establish and interpret meanings in their Environment and there are few important considerations about communication:

1. Different audiences and situation need different communication strategies.

2. People are aware of above drawbacks up to a varying degree.

3. Effective communicators are aware about the above two situations and behave in according with that.

1. Aristotle’s definition of rhetoric

2. Aristotle’s model of proof

3. Bitzer’s Rhetorical Situation

1. The Shannon-Weaver Mathematical Model, 1949

2. Berlo’s S-M-C-R, 1960

3. Schramm’s Interactive Model, 1954

1. Dance’s Helical Spiral, 1967

2. Westley and MacLean’s Conceptual Model, 1957

3. Becker’s Mosaic Model, 1968

1. Ruesch and Bateson, Functional Model, 1951

2. Barnlund’s Transactional Model, 1970

1. Systemic Model of Communication, 1972

2. Brown’s Holographic Model, 1987

3. A Fractal Model

4. Gricean Maxims

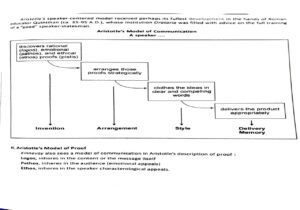

One of the earliest definitions of communication came from the Greek philosopher-teacher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.). “Rhetoric” is the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion’. Rhetoric. Is the art of speaking or writing effectively-as the study of principles and rules of composition formulate by critics of ancient times, and the study of writing or speaking as a means of communication and persuasion. Aristotle, now in clear terms of communication, mentioned about the communication that speak discovers rational, emotional, and ethical proofs, arranges those proofs strategically, clothes the ideas in clear and completing words and delivers the product appropriately.

Aristotle’s speaker-centered model received perhaps its fullest development in the hands of Roman educator Quintilian (ca. 35-95 A.D.), whose Institution Oratoria was filled with advice on the full training of a “good” speaker-statesman.

Kinnevay also sees a model of communication in Aristotle’s description of proof:

1. Logos, inheres in the content or the message itself.

2. Pathos inheres in the audience (emotional appeals).

3. Ethos inheres in the speaker characterological appeals.

Crude Shannon, an engineer for the Bell Telephone Company, designed the most influential of all early communication models. His goal was to formulate a theory to guide the efforts of engineers in finding the most efficient way of transmitting critical signals from one location to another. Later on, Shannon introduced a mechanism in the receiver which corrected for differences between the transmitted and received signal; this monitoring or correcting mechanism was the forerunner of the now widely used concept of feedback (information which a communicator gains from others in response to his own verbal behavior).

In the words of John Fiske, “Shannon and Weaver’s model is one which is widely accepted as one of the main seeds out of which Communication Studies has grown’. Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver were not social scientists but engineers working for Bell Telephone Labs in the United States. Their goal was to ensure the maximum efficiency of telephone cables and radio waves. They developed a model of communication which was intended to assist in developing a mathematical theory of communication. Their work proved valuable for communication engineers in dealing with such issues as the capacity of various communication channels in ‘bits per second’. It contributed to computer science. It led to very useful work on redundancy in language. And in making ‘information’ ‘measurable, it gave birth to the mathematical study of ‘information theory’. The problem is that some commentators have claimed that Shannon and Weaver’s model has a much wider application to human communication than a purely technical one. Shannon Weaver’s original model consisted of five elements:

1. An information source, which produces a message.

2. A transmitter, which encodes the message into signals.

3. A channel, to which signals are adapted for transmission.

4. A receiver, which ‘decodes’ (reconstructs) the message from the signal.

5. A destination, where the message arrives.

Noise is a dysfunctional factor – any interference with the message travelling along the channel such as ‘static on the telephone or radio) which may lead to the signal received being different from that sent.

The simplest and most influential message-centered model came from David K. Berlo. Berio’s S model was, essentially, an adaptation of the Shannon-Weaver model.

Wilbur Schramm was one of the first to alter the mathematical model of Shannon and Weaver. He conceived of decoding and encoding as activities maintained simultaneously by sender and receiver. He also made provisions for a two-way interchange of messages. Here, we can also notice the inclusion of a “interpreter” 3s an abstract representation of the problem of meaning.

Dance depicts communication as a dynamic process. According to Dance, “At all times, that helix gives geometrical testimony to the concept that communication while moving forward is at the same moment coming back upon itself and being affected by its past behavior, for the coming curve of the helix is fundamentally affected by the curve from which it emerges. Yet, even though slowly, the helix can gradually free itself from its lower-level distortions. The communication process, like the helix, constantly moving forward and yet is always to some degree dependent upon the past, which informs the present and the future. The helical communication model offers a flexible communication process”.

Westley and Maclean realized that communication does not begin when one person starts to talk, but rather when a person responds selectively to his immediate physical surroundings. Each interactant responds to his sensory experience (X1…) by abstracting out certain objects of orientation (X1…3m). Some items are selected for further interpretation or coding (X) and then are transmitted to another person, who may or may not be responding to the same objects of orientation (X,b).

Becker assumes that most communicative acts link message elements from more than one social situation in the tracing of various elements of a message, it is clear that the items may result in part from a talk with an associate, from an obscure quotation read years before, from a recent TV commercial, and from numerous other dissimilar situations-moments of introspection, public debate, coffee-shop banter, daydreaming and so on. In short, the elements that make up a message ordinarily occur in bits and pieces Some items are separated by gaps in time, others by gaps in modes of presentation, in social situations, or in the number of persons present.

Becker likens complex communicative events to the activity of a receiver who moves through a constantly changing cube or mosaic of information. The layers of the cube correspond to layers of information Each section of the cube represents a potential source of information; note that some are blocked out in recognition that at any given point some bits of information are not available for use. Other layer corresponds to potentially relevant sets of information.

Huesch and Bateson conceived of communication as functioning simultaneously at four levels of analysis. One is the basic intrapersonal process (level 1). The next level 2) is interpersonal and focuses on the overlapping fields of experience of two interactants. Group interaction (level 3) comprises many people. And finally, a cultural level (level 4) links large groups of people. Moreover, each level of activity consists of four communicative functions: evaluating, sending, receiving, and channeling. Notice how the model focuses less on the structural attributes of communication-source, message, receiver, etc.-and more upon the actual determinants of the process.

A similar concern with communication function can be traced through the models of Cornell (1959)

Fering (1953), Mysak (1970), Osgood (1954), and Peterson (1958) Peterson’s model is one of the the integrate the physiological and psychological functions at work in all interpersonal events.

The transactional approach taken by Barnlund, one of the few investigators who made explicit their assumptions on which his model was based, is mast systematic than functional model.

Its most striking feature is the absence of any simple or linear directionality in the interplay bet self and the physical world. The spiral lines connect the functions of encoding and decoding and graphic representation to the continuous, unrepeatable, and irreversible assumptions mentioned ear Moreover, the directionality of the arrows seems deliberately to suggest that meaning is actively assign or attributed rather than simply passively received.

Any one of three signs or cues may elicit a sense of meaning. Public cues (Cpu) derive from the environment. They are either natural, that is, part of the physical world, or artificial and man-made Private objects of orientation (Cpr) are a second set of cues. They go beyond public inspection or awareness. Examples include the cues gained from sunglasses, earphones, or the sensory cues of taste and touch. Both public and private cues may be verbal or nonverbal in nature. What is critical is that they are outside the direct and deliberate control of the interactants. The third set of cues are deliberate; they are the behavioral and nonverbal (Cbeh) cues that a person initiates and controls himself. Again, the process involving deliberate message cues is reciprocal. Thus, the arrows connecting behavioral cues stand both for the act of producing them-technically a form of encoding-and for the interpretation that is given to an act of others (decoding). The jagged lines (VVVV) at each end of these sets of cues illustrate the fact that the number of available cues is probably without limit. Note also the valence signs (+, 0, or -) that have been attached to public, private, and behavioral cues. They indicate the potency or degree of attractiveness associated with the cues. Presumably, each cue can differ in degree of strength as well as in kind. And, each end of these sets of cues illustrates the fact that the number of available cues is probably without limit. Note also the valence signs (+, 0, or -) that have been attached to public, private, and behavioral cues. They indicate the potency or degree of attractiveness associated with the cues. Presumably, each cue can differ in degree of strength as well as in kind.

Some communication theorists have attempted to construct models in light of General System Theory. The “key assumption” of GST “Is that every part of the system is so related to every other part that any change in one aspect results in dynamic changes in all other parts of the total system. It is necessary then, to think of communication not so much as individuals functioning under their own autonomous power but rather as persons interacting through messages. Hence, the minimum unit of measurement that which ties the respective parties and their surroundings into a coherent and indivisible whole.

1. The Impossibility of Not Communicating: Interpersonal behavior has no opposites. It is not possible to conceive of non-behavior. If all behavior in an interactional situation can be taken as having potential message value, it follows that no matter what is said and done, “one cannot communicate. Silence and inactivity are no exceptions. Even when one person tries to ignore the overtures of another, he nonetheless communicates a disinclination to talk.

2. Content and Relationship in Communication: All face-to-face encounters require some sort of personal recognition and commitment which in turn create and define the relationship between the respective parties. “Communication,” wrote Watzlawick, “not only conveys information, but… at the same time… imposes behavior.” Any activity that communicates information can be taken as synonymous with the content of the message, regardless of whether it is true or false, valid or invalid…. Each spoken word, every movement of the body, and all the eye glances furnish a running commentary on how each person sees himself, the other person, and the other person’s reactions.

3. The Punctuation of the Sequence of Events: Human beings “set up between them patterns of interchange (about which they may or may not be in agreement) and these patterns will in fact be rules of contingency regarding the exchange of reinforcement”.

4. Symmetrical and Complementary Interaction: A symmetrical relationship evolves in the direction of heightening similarities; a complementary relationship hinges increasingly on individual differences… The word symmetrical suggests a relationship in which the respective parties mirror the behavior of the other. Whatever one does, the other tends to respond in kind. Thus, an initial act of trust fosters a trusting response; suspicion elicits suspicion; warmth and congeniality encourage more of the same, and so on. In sharp contrast is a complementary relationship, where individual differences complement or dovetail into a sequence of change. Whether the complementary actions are good or bad, productive or injurious, is not relevant to the concept.

Rhetorical theorist, William Brown, proposed “The Holographic View of Argument”. Arguing against an analytical approach to communication that dissects the elements of communication, Brown argued for seeing argument or communication as a hologram “which as a metaphor for the nature of argument emphasizes not the knowledge that comes from seeing the parts in the whole but rather that which arises from seeing the whole in each part. The ground of argument in a holographic structure is a boundaryless event. A model of communication based on Brown’s holographic metaphor would see connections between divided elements and divisions between connections.

Polish-born mathematician, Benoit Mandelbrot, while working for IBM in the 1960s and 70s, became intrigued with the possibility of deriving apparently irregular shapes with a mathematical formula. “Clouds are not spheres,” he said, “mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not for nor does lightning travel in a straight line.” So if these regular geometric forms could not account for natural patterns, what could?

To solve the problem, Mandelbrot developed the fractal, a simple, repeating shape that can be created by repeating the same formula over and over.

“I coined fractal from the Latin adjective fractus. The corresponding Latin verb frangere means ‘to break’: to create irregular fragments. It is therefore sensible-and how appropriate for our needs!-that, in addition to “fragmented’ fractus should also mean irregular, both meanings being preserved in fragment.”

Construction of a Fractal Snowflake: A Koch snowflake is constructed by making progressive additions to a simple triangle. The additions are made by dividing the equilateral triangle’s sides into thirds, then creating a new triangle on each middle third. Thus, each frame shows more complexity, but every new triangle in the design looks exactly like the initial one. This reflection of the larger design in its smaller details is characteristic of all fractals. Fractal shapes occur everywhere in nature: a head of broccoli, a leaf, a snowflake-almost any natural form. Mandelbrot’s discovery changed computer graphics-by using fractal formulas, graphic engines could create natural-looking virtual landscapes. More importantly, fractal formulas can account for variations in other natural patterns such as economic markets and weather patterns.

Mandelbrot Set: Polish-born French mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot coined the term “fractal” to describe complex geometric shapes that, when magnified, continue to resemble the shape’s larger structure. This property, in which the pattern of the whole repeats itself on smaller and smaller scales, is called self-similarity. The fractal shown here, called the Mandelbrot set, is the graphical representation of a mathematical function.

Fractals allow for almost infinite density. For example, Mandelbrot considered the deceptively simple question: “How long is the coast line of Britain?” A typical answer will ignore inlets and bays smaller than a certain size. But if we account for these small coastline features, and then those smaller still, we would soon find ourselves with a line of potentially infinite and constantly changing length. A fractal equation could account for such a line.

Applying Fractals to Communication: Like Dance’s Helix, seeing communication as a fractal form allows us to conceptualize the almost infinite density of a communication event. Margaret J. Wheatley has attempted to apply Fractal theory and the science of chaps to management.

The significance of this for the topic at hand is this: First, the patterns of complexity in natural systems, of which human beings are a part, is profoundly complex and not easily captured in any formula. Therefore, any predictions about the outcome of these systems are necessarily limited because of the difficulty of being sensitive to initial conditions. A model of communication drawn from fractals and chaos theory would have to reflect this complexity and respond to variations in initial conditions.

Herbert Paul Grice (March 13, 1913, Birmingham, England – August 28, 1988, Berkeley, California), usually publishing under the name H. P. Grice, H. Paul Grice, or Paul Grice, was a British-educated philosopher of language, who spent the final two decades of his career in the United States. Grice understood “meaning” to refer to two rather different kinds of phenomena. Natural meaning is d to capture something similar to the relation between cause and effect, as, for example, applied supposed in the sentence “Those spots mean measles. This must be distinguished from what Grice calls nonnatural meaning, as present in “Those three rings on the bell (of the bus) mean that the bus is full”. Grice’s subsequent suggestion is that the notion of nonnatural meaning should be analyzed in terms of speakers’ intentions in trying to communicate something to an audience.

In his book studies in the Way of Words, he presents what he calls “Grice’s Parador”. In 1, he supposes that two chess players, You and Zog, play 100 games under the following conditions:

1. Yog is white nine of ten times.

2. There are no draws

And the results are:

1. Yog, when white, won 80 of 90 games.

2. Yog, when black, lost ten of ten games,

This implies that:

1. 8/9 times, If Yog was white, Yog won

2. 1/2 of the time, if Yog lost, Yog was black.

3. 9/10 times, either Yog wasn’t white or he won

But by contraposition and conditional disjunction:

(1 from 2) If Yog was white, then 1/2 of the time Yog won.

(2 from 3) 9/10 times, if Yog was white, then he won.

Both (1) and (2) contradict (1).

In the course of his investigation of speaker meaning and linguistic meaning, Grice introduced a number of interesting distinctions. For example, he distinguished between four kinds of content: encoded /non-encoded content and truth-conditional/non-truth-conditional content.

1. Encoded content is the actual meaning attached to certain expressions, arrived at through; Investigation of definitions and making of literal interpretations.

2. Non-encoded content are those meanings that are understood beyond an analysis of the words themselves, i.e., by looking at the context of speaking, tone of voice, and so on.

3. Truth-conditional content are whatever conditions make an expression true or false.

4. Non-truth-conditional content are whatever conditions that do not affect the truth or falsity of an expression.

Sometimes, expressions do not have a literal interpretation, or they do not have any truth-conditional content, and sometimes expressions can have both truth-conditional content and encoded content.

For Grice, these distinctions can explain at least three different possible varieties of expression:

1. Conventional Implicature: When an expression has encoded content, but doesn’t necessarily have any truth-conditions;

2. Conversational Implicature: When an expression does not have encoded content, but does have truth-conditions (for example, in use of irony);

3. Utterances: When an expression has both encoded content and truth-conditions.